Racism Exists Everywhere | South Asia and Racism

- Content Creators

- Aug 8, 2020

- 8 min read

Updated: Aug 9, 2020

Multiple Authors | South Asia

Note from the Editors: The Black Lives Matter Movement has sparked a global conversation about racial injustice and inequalities not just in the United States, but globally. The conversation must continue, and part of that means reflecting on our own biases and acknowledging changes that need to be made within our own communities. For the months of June and July, we asked our Contributing Writers to reflect on racism and inequality, specifically within the context of South Asia (where our writers are based). This article compiles their insights on the topic.

Part 1

Maliha Khan | Srinagar, Kashmir

As the Black Lives Matter Movement has become more prominent again in the past few months, another phrase that was commonly heard was “but I’m not a racist”.

Where does that phrase come from? What makes a person racist or not? Is racism only limited to an active display of colour based discrimination or is there a passive display and a subconscious learning of a racist behaviour as well?

The repeated use of the former phrase in the past few months clearly displays the widespread ignorance and a lack of acknowledgement of racism being entrenched in our society. The past months have also made clear that our common definitions of racism are flawed. We usually focus on individual overt acts of racism while mostly ignore the institutionalized racism that is a part of our daily lives. When it is this institutionalized and covert racism entrenched into our social systems that leads to individual acts of racism.

This covertness is much more significant when we move towards South Asia. Usually, when we talk about racism, we tend to focus on it in an American context. This gives us a very limiting and a narrow sense of racism especially when we consider the South Asian community. Unlike America or many Western countries where comparatively racism is a very familiar concept to the general public, regardless of their stance on it, the South Asian community largely is yet to get familiar with or even recognize this phenomenon.

It is this vagueness and covertness of racism in countries like India and Pakistan that makes it difficult and dangerous. Racism has camouflaged into our culture, lifestyle and behaviours so much so that pointing out racist acts and ideology is a struggle in itself.

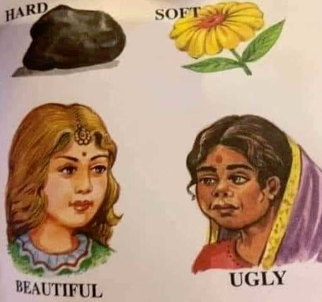

This idea of white supremacy is implanted into our minds throughout various stages of socialization, beginning from childhood. A few years back I came across a textbook for kindergarten children where pictures were used to describe things. What caught my eye was that a woman of a light skin tone was described as beautiful while as to define ugly, picture of a woman with a darker skin tone was used. These messages are thus internalized right from the beginning and get normalized in society.

The inability of the South Asian society to recognize their racism was clear with the black lives matter movement, when thousands in the subcontinent extended their support to the movement in America but were called out for their hypocrisy. While they condemned racism in America, their daily vocabulary, behaviours and beauty ideals were quite racist. Casually calling their dark-skinned friends “kaala” (black), putting up demands such as fair-skin in matrimonial ads, and upholding the caste system which is rooted in white supremacist ideology, are all acts of racism which society chooses to overlook.

Film actors were found guilty of this hypocritical behaviour most of all. It was quite ironic to see Bollywood celebrities denouncing racism in America and posting #blacklivesmatter on social media when these very celebrities endorse skin whitening creams. The actors who condemned anti-black sentiments in America for years have propagated the idea of “white is better” in their home countries and led the audiences, especially girls, to believe that their natural skin tone is not beautiful. The film and TV industries in the subcontinent have not only glorified white skin colour but also solidified the culture of colourism through stereotypes, racist jokes, etc.

Clearly, we no longer can deny the existence of racism in the subcontinent. It has permeated across the society and seeped deep into our social fabric. We first have to identify racism and then work towards its eradication.

Which again brings me back to the question of what is considered racist. Racism is much broader than just the issue of colourism and anti-black sentiment. It is prejudice and the resulting discrimination against any race. And COVID-19 pandemic has brought this to light. Since the pandemic has started there has been a significant increase in racism against East Asians and people of Asian descent across globe. And I say increase because it existed before the pandemic as well. People form East Asia and those tracing their descent from East Asia around the world have been met with ill-treatment, verbal abuse and xenophobia for years and has only grown due to the coronavirus pandemic. Within Asia, people particularly from East Asia face racism in countries such as India, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

Because we are talking of the Indian subcontinent, it would be unfair to not talk about the racism and prejudice faced by the North-Eastern Indians at the hands of the rest of the Indian population. From being called stereotypical and derogatory names to being physically and verbally attacked, they have faced everything. Furthermore, with the advent of the coronavirus the treatment has only gotten worse. There have been instances were the have been called corona and spat at. All of this, just because of the way they look.

We have lived and continue to live in a world where people are judged and consequently treated based on what they look like. The black lives matter movement is undoubtedly a turning point in today’s world, which hopefully will be a significant step for our societies to rise above the trivial distinctions like race and colour.

Coming back to the phrase I began with “But I’m not a racist”, at this point of time we need to reevaluate what we understand by racism. But most importantly in today’s age not being racist is not enough to be against racism. To be truly supportive of the cause you have to be actively anti-racist.

Part 2

Tehreem Khan | Hyderabad, Pakistan

In 2013, Pakistan was chosen to be one of the most “racially tolerable countries” by a report in the Washington Post (https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2013/05/15/a-fascinating-map-of-the-worlds-most-and-least-racially-tolerant-countries/). If you look at Pakistan as a bigger picture this statement is definitely true. This is because 97% of the people in Pakistan are Muslims, and Islam does not promote racism. Above all, Pakistanis believe in hospitality towards people irrespective of their religion, caste or culture.

Despite the fact that it is accounted as a very accepting country, there is still the presence of prejudice. In Pakistan, racism is so incorporated into our minds that we often make comments without noticing their implications. The terms “gora chitta” and “surk safaid” (white) is often associated with a beautiful physical appearance and the words “kalla kola” (black coal) is used as an insult. The concept that beauty is only related to clear or fair complexions fuels racism and insecurities among people. Nobody wants a bride or husband who isn’t "fair-skinned". All of this is further promoted by our multi-million dollar skin whitening companies who go on to advertise products which are supposed to “whiten” your skin. Often good looking or “fair people” are given more chances in workplaces or schools because of their visual appearance, too.

Other than that many castes in Pakistan are often surrounding by baseless stereotypes. For example, Pashtuns are considered “wild, aggressive and illogical”, Punjabis are considered “cunning”, Sindhis are considered to be “messy”. Although none of these stereotypes have any logical basis or truth associated with them, people often judge or joke about other people based on these stereotypes.

The majority of Pakistanis don’t even bat an eye about minorities and consider them as their equals or family, but there are still sick-minded people who carry out violent attacks on Pakistan’s religious minorities. Women belonging to minority groups are blackmailed into forced marriages and conversion. Many people carry out destruction of churches and temples.

The good news is that the new generation has started to bring up and bring an end to this problem. As levels of education and understanding are starting to grow and prevail, there is an increase in understanding human rights and equality in Pakistan and that has brought hope for the future.

Part 3

Ammara Maqsood | Mandi Bahauddin, Pakistan

The esteemed person who struggled for independence from British Raj was the supporter of the phrase "All citizens are equal." It is very sad that intolerance and bigotry in Pakistan is rising by each passing day among some people. This type of mindset results in hostilities.

In the past, there were some leaders who played the religion card to gain more power. In the process, Sikh, Hindu and Christian communities in Pakistan were sometimes ignored. Dictator General Zia called himself "the soldier of Islam." He enforced extremism which was not in line with the Islamic values of tolerance and peace building in communities.

In contemporary Pakistan, there are some positive changes being implemented by the government. This includes the inauguration of the Kartarpur corridor, which is a holy site for Sikhs which was previously inaccessible to the Sikh community of India and has now been opened for them to visit with amazing facilities. There is also a quota for minorities in an effort to ensure they are represented in the civil services examination and other educational institutions.

Despite these changes, there are still shifts to our mindset which need to happen. There was a recent incident in which the construction of a temple was stopped in Islamabad. The Shia community (members of sect of Islam) also face backlash by some groups of people. While the government is trying to make Pakistan more secular, and ensure that minority groups are given equal treatment, there are some members of the public who are making this effort much more difficult. Ultimately, just like anywhere in the world, Pakistan does have its fair share of individuals who hold prejudice about people who belong to other religions, races or cultures, and there is a need to shift the mindset to end any extremism, bigotry and intolerance that does exist in the country.

Part 4

Ayesha Mahmood | Sargodha, Pakistan

Racism exists in so many ways, in different countries, in different areas. Racism, just like prejudice of all forms, has allowed the world has created dichotomies of who is superior and inferior on the basis of people's race. Not only that, but people's wealth, level of education, or the way they dress can all be reasons for using stereotypes and having prejudice against others.

In Pakistan, although there are those that try to give rights to minorities, there are still incidents in which people burn the houses of Christians if they come to live in their area, claiming that they are "na-pak" (meaning impure in Urdu). People are killed for not converting to Islam. What's so wrong about this, is not only that it is an inhumane thing to do, but also that the religion which the perpetrators of this violence follow (Islam) preaches that they should do exactly the opposite. In the Quran (our holy book), it is clearly written, “No person has superiority over other, except on the basis of Taqwa (piety)”. In Islam, it is also said that killing one person is equivalent to killing all of humanity, and so it is one of the biggest sins someone can commit. Clearly, the people who let prejudice and racism guide their actions are not following Islam, a religion that is against hatred or using violence against others.

Humanity should be our top priority. But people have left no stone unturned in hurting others on the basis of their religion, race, and even their physical disabilities. The prejudice that we as humans hold are just things that our minds have created in us. Ultimately, all people are equal regardless of their color, religion, or abilities. If everyone understood this, then issues like racism would not exist, and so many people's suffering which has come as a result of this would end.

.png)

Comments